Career-development theorists tend to ignore one of the most basic facts of life—that while people are busy making a living, they are living a life. The result is that many theorists describe career development as if it occurred in isolation from human development. Isolating life roles creates a false scenario that does not reflect life as people live it. Career interventions emanating from false scenarios have limited usefulness as clients leave career counseling and attempt to implement their work-related decisions within a complex web of life-role activities. When career counselors ignore their clients’ multiple life-role activities, they also ignore the fact that life roles can interact in ways that are supportive, supplementary, complementary, or conflicting. Life roles can enrich life or overburden it. Donald Super noted that for each person, the social elements that constitute a life are arranged in a pattern of core and peripheral roles. This pattern is defined as the life structure. The life structure organizes and channels the person’s engagement in society. To understand an individual’s career, it is important to know and appreciate the web of life roles that embeds that individual and her or his career concerns.

Career-development theorists tend to ignore one of the most basic facts of life—that while people are busy making a living, they are living a life. The result is that many theorists describe career development as if it occurred in isolation from human development. Isolating life roles creates a false scenario that does not reflect life as people live it. Career interventions emanating from false scenarios have limited usefulness as clients leave career counseling and attempt to implement their work-related decisions within a complex web of life-role activities. When career counselors ignore their clients’ multiple life-role activities, they also ignore the fact that life roles can interact in ways that are supportive, supplementary, complementary, or conflicting. Life roles can enrich life or overburden it. Donald Super noted that for each person, the social elements that constitute a life are arranged in a pattern of core and peripheral roles. This pattern is defined as the life structure. The life structure organizes and channels the person’s engagement in society. To understand an individual’s career, it is important to know and appreciate the web of life roles that embeds that individual and her or his career concerns.

Increasingly, career-counseling clients, especially adult clients, present for career counseling due to life structure concerns. For example, in career counseling, an adult client may come to understand that her conflict regarding selecting a more satisfying career option is connected to the pressure she experiences as a parent of young children. Similarly, the young adult college student may desperately desire to switch her academic major from engineering to education but is afraid to do so because she does not want to disappoint her parents, who seem intent on their daughter’s becoming an engineer. Rarely do decisions about work occur in isolation from other life-role experiences.

Life-structure concerns can involve normal developmental processes (such as the college student attempting to sort out career decisions within the individuation process), but they can also involve unexpected and traumatic life events (e.g., unexpected job loss). Developmental life-structure concerns are predictable (e.g., the graduating college student must prepare for “life after college”) and therefore can be addressed via career counselors constructing developmental career-intervention programs. Professional counselors in the schools take this approach when they offer evening programs for parents and students regarding topics such as financial aid for postsecondary education, college planning, and career fairs. Counselors in higher education do the same when they offer workshops on selecting a major for first-and second-year university students and job-search workshops for fourth-year students. Career interventions such as these seek to address the predictable career-development tasks Super outlined in his life stage theory segment.

Life-structure concerns can also be unpredictable, as when a partner or parent dies unexpectedly, a serious illness arises, an unplanned job loss occurs, or an injury requires a substantial shift in life-role activities (although these examples are not necessarily equal in the trauma they generate, they each require adjustments to one’s life structure). Interventions at these times tend to be more therapeutic (than what is typically required to address developmental concerns) and often require individual career-counseling interventions. Collectively, developmental and traumatic events influence the life structure throughout the life span, making life-role choices and adjustment to choices continuous processes.

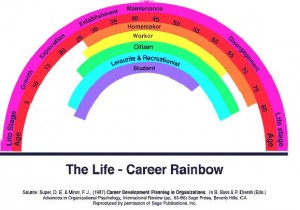

In describing the life structure, Super identified nine primary life roles: child, student, worker, partner, parent, citizen, homemaker, leisurite, and pensioner. He also noted that each life role tends to be played in a particular theater, such as the home, school, work, or community. In today’s environment, life roles are often played in multiple theaters. For example, laptop computers make it possible to work in a park or at home. The role of student can be played at school or at home, as in the case of Web-based training courses. Thus, the fluidity of life-role activities has increased to the point where individual theaters commonly contain multiple roles. This fluidity makes balancing life-role activity an even greater challenge.

The blurring of boundaries between roles and theaters also requires us to be intentional in our life-role behavior and, at times, to communicate our intentions to others. For example, engaging in conversation with a friend may be acceptable when we are enjoying a leisurely latte in a coffee shop, but not acceptable when we have chosen the coffee shop as the location for completing a business report in a timely manner. It may be difficult for one’s friends to know the life role (worker or leisurite) one is engaging in unless they are told. The blurring of boundaries between roles and theaters requires a greater emphasis on communicating our activities to others.

Using the Life-Career Rainbow

As implied, life roles influence each other, so the same job will hold different meanings for two individuals who live in different situations. Career counselors help their clients clarify and articulate the interests, abilities, and values they seek to express in the life roles that are important or salient to them. Role salience comprises cognitive, behavioral, and affective dimensions. Salience is strongest when we have knowledge about a life role (cognitive), participate in it (behavioral), and feel that the role is important (affective). When one dimension is weak, the implication is that salience is weaker. For example, if it is stated that a life role is important (e.g., leisure) but we know little about it and spend little time participating in it, the implication is that salience for that role is weak. When the three dimensions of role salience hold similar levels of importance for a particular role, career interventions often focus on helping clients identify outlets for engaging in that life role. When any of the dimensions of role salience are discordant, career interventions often address the reasons for this discordance. For example, if the affective dimension is strong but the behavioral dimension is weak (i.e., the client says that he feels the role is important to him but does not spend time in that life role), career counseling focuses on factors underlying this discrepancy. Solutions for the client may lie in adjusting one dimension or the other (e.g., the role is not as important as he thought, or the role is important and he needs to find opportunities for greater engagement in the role).

To address such issues related to the life structure, Super devised the Life-Career Rainbow. The Rainbow provides a graphic device that merges Super’s “lifespan, life-space” theory segments. There are multiple dimensions to the Rainbow. The outer band of the Rainbow depicts the longitudinal dimension (i.e., life span) of career development. It begins in the lower left, with birth, and proceeds to move left to right across the Rainbow chronologically, often extending three to five years into the person’s future. This reflects what Super labeled as the maxicycle of career development. Although this dimension of the Rainbow was initially connected to the career-development stages of Growth (childhood), Exploration (adolescence), Establishment (young adulthood), Maintenance (middle adulthood), and Disengagement (late adulthood), it is now acknowledged that career development in adulthood rarely proceeds in a linear fashion and that the stages tend to be a reflection, regardless of age, of the multiple career-development tasks confronting people (sometimes concurrently) as they attempt to manage their careers throughout the life span. Thus, age becomes more relevant than stage within the Life-Career Rainbow activity, and career-development tasks provide indications of the career resources clients need to effectively cope with the challenges they confront.

Above the Rainbow, and at the center, Super identifies the situational determinants (e.g., history, socioeconomic status, family of origin, country of residence) that influence our life-role self-concepts and life-role activities. Below the Rainbow, and at the center, Super identifies the personal determinants that influence our development (e.g., psychological and biological factors). Collectively, personal and situational determinants remind us that context influences careers. Personal and situational factors interact to shape our life-role self-concepts and to present us with career-development tasks, with which we must successfully cope to manage our career development effectively.

Career counselors use the Rainbow in individual and group career counseling. The starting point involves asking clients to construct their personal Rainbows. Beginning with birth, clients construct individual strands for each life role in which they have participated. Clients proceed to construct the strands of their Rainbow from the past to the present. The size of a strand increases or decreases at any point in time to reflect the person’s degree of involvement in the role at specific points in time (e.g., leisure may decrease as work involvement increases and parenting becomes a part of a person’s life structure).

Career counselors often focus on exploring clients’ experiences of their current life structures as reflected in their Life-Career Rainbows. Exploring what clients find satisfying or dissatisfying about their current life structures often provides important information as to how clients would like to move forward in their lives. Introducing interests, abilities, and values into the process can occur when the career counselor asks the client to consider the interests, abilities, and values reflected in the life-role activities depicted in the client’s Rainbow. When life-role activities restrict the expression of these core client characteristics, the client is encouraged to identify outlets for increasing the expression of core interests, abilities, and values in current and future life-role activities.

Projecting the Rainbow three to five years into the future also stimulates goal-related discussions in career counseling that seek to identify opportunities for engaging in life-role activities that provide outlets for interests, abilities, and values expression. Providing the client with stimulus questions related to life-role activities the client would prefer to increase and/or decrease is an important activity for constructing the future Rainbow. Then, the counselor and client identify strategies for increasing the probability of the future Rainbow occurring. Short-term and long-term steps are identified.

Additional career-counseling questions for clients to consider when reviewing their Life-Career Rainbow include the following:

- How do you spend your time during a typical week?

- How important are the different roles of life to you?

- What activities do you engage in to learn more about the life roles that are important to you?

- What do you like about participating in each of the life roles?

- What life roles do you think will be important to you in the future?

- What do you hope to accomplish in each life role that will be important to you in the future?

- What life roles do members of your family play?

- What do your family members expect you to accomplish in each life role you play?

Conclusion

Effective life-role participation is difficult to achieve. Conflicting life-role demands make effective life-role participation seem like a moving target. Life is best when life roles nurture each other and offer opportunities for people to express their core interests, abilities, and values. Life becomes stressful when life roles collide and provide little opportunity for expressing core characteristics. Super contended that the life structure, once designed, is not static; it runs a developmental course and then needs redesign. The Life-Career Rainbow embraces this fact by providing a vehicle for focusing on how clients structure the basic roles of work, play, friendship, and family into a life.

See also:

- Crystallization of the vocational self-concept

- Personal Globe Inventory

- Self-awareness

- Self-concept

- Super’s career development theory

References:

- Niles, S. G., Anderson, W. P., Hartung, P. J. and Staton, A. 1999. “Identifying Client Types from Adult Career Concerns Inventory Scores.” Journal of Career Development, 25:173-185.

- Super, D. E. 1980. “A Life-span, Life-space Approach to Career Development.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 13:282-298.

- Super, D. E. “Career and Life Development.” Pp. 192-234 in Career Choice and Development, 3d ed., edited by D. Brown, L. Brooks, and Associates, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Super, D. E., Savickas, M. L. and Super, C. M. 1996. “The Life-span, Life-space Approach to Careers.” Pp. 121-178 in Career Choice and Development, 3d ed., edited by D. Brown, L. Brooks, and Associates. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.