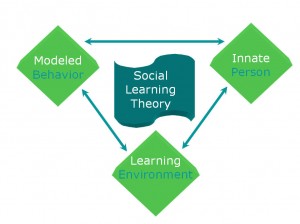

People work at an incredibly wide number of jobs. A major question is How can we explain how people find their way into working at one occupation rather than another? The social learning theory of career development (SLTCD) is one of a number of theories that help explain how individuals make occupational choices. The SLTCD attributes occupational placement to an uncountable number of learning experiences, some planned but most unplanned, that influence the path through the occupational maze. Unlike traditional career counseling models, which aim to assist clients in making a decision about a career path, the SLTCD welcomes indecision as a sensible approach to a complex and unpredictable future. Career counselors can help clients reframe indecision as open-mindedness.

People work at an incredibly wide number of jobs. A major question is How can we explain how people find their way into working at one occupation rather than another? The social learning theory of career development (SLTCD) is one of a number of theories that help explain how individuals make occupational choices. The SLTCD attributes occupational placement to an uncountable number of learning experiences, some planned but most unplanned, that influence the path through the occupational maze. Unlike traditional career counseling models, which aim to assist clients in making a decision about a career path, the SLTCD welcomes indecision as a sensible approach to a complex and unpredictable future. Career counselors can help clients reframe indecision as open-mindedness.

The world is extremely complex. No one knows what the future will hold. No one knows how interests will change, how new occupations will arise, or how new opportunities will be created. The SLTCD states that people should not expect to know exactly what they will be doing nor where they will be doing it in the future. Instead it advocates that people can create opportunities by their own actions. Individuals may not know in advance how their actions will generate opportunities, but it is quite clear that doing nothing creates nothing. Unexpected events arise when action is taken. New people are met, new activities are tried, and feedback is gained from every activity that is tried.

Placing Greater Value On Happenstance

Unplanned events and chance encounters often determine the paths individuals take both in their personal and their professional lives. In the SLTCD, happenstance is seen as more than random occurrences; it is an outcome of earlier decisions and behaviors, and it is a valuable tool that prompts clients to take actions or make decisions that may have life-altering effects.

The SLTCD recognizes that many circumstances and events in clients’ lives are out of their control. Genetic and environmental factors that influence clients’ lives are good examples of circumstances in which they have little, if any, control.

Gaining Greater Control Over Happenstance

The SLTCD acknowledges that, although many events are out of clients’ control, clients can actually create, recognize, and take advantage of these unplanned events. Counseling clients to keep an open mind and to recognize the opportunities afforded them when they encounter unexpected events can make a dramatic difference in the direction their career paths will take.

Take Thomas, for example. He was born into a large, loving family that taught him to be honest, hard working, and respectful of others. His parents did not have much money; however, they emphasized the value of learning. Thomas developed an early interest in mathematics. He learned how to count to 100 before he reached the age of 3, and by the time he was 10 years old, he was ahead of his entire math class and often found the class boring. In the fifth grade, Thomas’s teacher realized that he needed a greater challenge and asked if he would like to tutor a few of his classmates during the weekly independent study hour. Thomas learned that he enjoyed helping his classmates master new mathematical skills.

It is not known why Thomas excelled in mathematics. Maybe his parents taught him to count at an early age. Maybe there is some genetic origin. He was fortunate to have a teacher who saw his potential and asked him to tutor. He seized that opportunity and found that he liked teaching others.

Reframing Unplanned Events As Career Opportunities

The SLTCD orients clients to view past experiences as lessons for present actions. Unplanned events can be seen as career opportunities—not just unexplained accidents. Explicit attention should be paid to the client’s desire for a satisfying life. Since each

person defines a satisfying life in different ways, it is important for career counselors to listen carefully to clients and encourage them to describe activities, both past and present, that energize them. Career counselors can teach clients that they need to recognize the potential opportunities in unplanned events.

Once clients understand how all of their experiences in life affect their decisions, they will see how each decision opens up the potential for new, often unexpected, events. Career counseling is much more complex than merely identifying a suitable occupation for a client. Career counseling today, in a time of uncertainty due to mergers, acquisitions, downsizings, and outsourcing, requires clients to embark on a journey of self-discovery and lifelong learning.

Transforming Action Into Learning

Learning can be defined as either instrumental or associative. Instrumental learning occurs when a person takes action and observes the consequences of that action. Consequences might include comments from other people, observable results, or impact on others. Thomas learned that excelling in math had positive rewards. He enjoyed seeing his classmates improve as a result of his tutoring, and he felt good about the recognition he received from his teacher.

Associative learning occurs when a person makes connections between two phenomena or stimuli. Learning results from observation and conditioning; for example, watching and listening to other people and observing the positive rewards or punishment they receive from certain actions. Thomas observed that competence and enjoyment seemed to go together. He noted that some of his classmates could start out hating math while getting poor grades but then learned to like it after they understood it.

Recognizing The Influence Of Genetic Factors And Environmental Conditions

Genetic factors and environmental conditions, such as physical attributes and abilities (or disabilities), talents, aptitudes, birth family, birth location, and family resources work together with learning experiences to form a client’s individual task approach skills. These skills include the ways in which clients cognitively process the world around them, including their beliefs, values, attitudes, feelings, work habits, goals, and expectations.

As a result of Thomas’s early experiences tutoring his peers, he developed the ability to communicate technical information in a way that was easy for others to understand. Thomas came to value the relationships he fostered, and he developed respect for people who desired to learn.

Making Self-Observations And Evaluations

A lifelong journey of learning depends upon self-observation and evaluation. Clients make generalizations about their performance in relation to the performance of others or in relation to their own past performance. In addition, clients evaluate whether they fulfilled or exceeded their own personal expectations or standards. Clients also generalize about their interests based on the activities they find enjoyable or challenging and about what is important to them and what brings them the most personal satisfaction.

Generalizations may be contextual, that is, dependent on the situation or others present when a learning experience occurred. Self-observation generalizations may or may not be accurate or consciously expressed. Thomas made the accurate self-observation generalization, “I am very good at math.” After dropping one fly ball while playing baseball, he might have generalized inaccurately, “I am a terrible athlete.” These self-observation generalizations can have a powerful effect on subsequent actions.

By the time he reached high school, Thomas generalized that he was excellent in math and was encouraged by his high school counselor to apply to a math and science college. He applied and was accepted at MIT. However, his math teacher told Thomas that the competition would be greater at MIT because almost all the students were excellent at math and science. Thomas began to worry about whether he could succeed at college.

Estimating Probability Of Success In Specific Occupations

Learning experiences and the generalizations they engender enable clients to make estimates, rightly or wrongly, about the probability of succeeding or enjoying a specific career. From their experiences and interactions with others, clients develop interests, coping strategies, ethics, values, and standards. Clients’ limited exposure to the world of work may lead them to assume that certain occupations value or require skills and interests that they may, or may not, have developed. Consequently, clients may initiate an education program or take a job that may, or may not, satisfy them. Career counselors need to help their clients think about their actions as experiments. If the first educational major or work experience is not satisfactory, then the career counselor can encourage clients to take alternative actions.

Recognizing That Environments And Interests Are Constantly Changing

Unlike previous generations who remained at the same job with the same company until retirement, today’s workers often make multiple career changes during their lifetime. When companies unexpectedly merge, for example, persons who had initially expected to have secure employment may find that their jobs are no longer required or that there is an overlap with jobs in the other company. As a result some people will either have to leave or move into new positions. Unplanned events are a common occurrence in life, and how clients respond to them will determine whether their lives are filled with opportunity and adventure or with obstacles and disappointment.

The constant advancement of technology is producing new and unexpected products and services. Occupations that once existed, for example, elevator operators or typewriter repairpersons, are now virtually obsolete. However, people previously employed in one of these occupations can generate new interests and learn how to adapt their skills to fit into current employment needs.

Interests are learned and new experiences provide opportunities for people to discover new interests.

During his first semester, Thomas was invited by one of his professors to join the math club. Through membership in the math club, Thomas met an impressive scholar who introduced him to the complex world of computer science. After learning more about computers and how they are designed, Thomas changed his major from mathematics to electrical engineering.

Emphasizing Lifelong Learning

Clients must not see their lack of a career plan as indecision but instead celebrate it as open-mindedness. People have a variety of learning experiences, both planned and unplanned, as a result of the happenstance events they encounter. Career counselors must prepare clients for a counseling process that embraces happenstance as a necessary component. Counselors should ask clients to identify past instances of happenstance in their lives, examine specific actions that created these unplanned events, and then initiate new actions to generate further unplanned events. Clients should be encouraged to see unexpected events as opportunities for learning and exploration. Career counselors should point out that clients can initiate action that will actually create more chance events using their successes with prior happenstance events as evidence that the clients already know how to do it.

Specific client actions that might lead to career opportunities include researching a job opening or company, volunteering to work at a nonprofit organization, attending a seminar or training program, talking with friends or relatives about job concerns and aspirations, and interviewing or job shadowing someone employed in a field of interest to establish new contacts. Actions like these can be meaningful ways of learning more about interests and generating unexpected valuable information. Counselors need to support client action and, if necessary, address any blocks that may inhibit clients from taking risks.

Genetics and environmental factors combine to produce clients’ perceptions of how the world is changing and how those changes produce career opportunities. Clients make generalizations on the basis of their observations of their own performance—both past and present. They use these generalizations to estimate their chances of success in various fields of endeavor. Since environments and client interests are constantly changing, career counselors need to help keep clients from becoming stuck in an initial job that may no longer be satisfactory and to see the opportunities that unexpected events create.

Thomas earned his PhD and was subsequently hired to teach engineering at a midwestern university. After 10 fulfilling years of teaching, Thomas’s father became ill and passed away. Thomas took a sabbatical leave and returned to his hometown to help his mother with the family farm. Thomas found that he enjoyed the outdoor life and experienced a sense of purpose and pleasure while gardening. When the owner of a local market asked Thomas if he would be interested in selling some of his organic produce, Thomas took advantage of the opportunity. Within a year, Thomas expanded his organic garden and began teaching others how to grow healthful produce using natural fertilizers and pest control.

Although Thomas had been very satisfied with his teaching career, the unexpected death of his father required that he make changes in his life. Thomas returned to his family farm with an open mind and soon discovered an interest in gardening. From the time Thomas was a young boy, he knew that he enjoyed teaching. However, Thomas could not have predicted that one day he would be teaching others how to garden.

By remaining open to new learning experiences and by making self-observations, Thomas found a second career that was satisfying to him and beneficial to the members of his community.

See also:

References:

- Krumboltz, J. D. 1992. “The Wisdom of Indecision.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 41:239-244.

- Krumboltz, J. D. 1996. “A Learning Theory of Career Counseling.” Pp. 55-80 in Handbook of Career Counseling Theory and

- Practice, edited by M. L. Savickas and W. B. Walsh. Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black.

- Krumboltz, J. D. and Levin, A. S. 2004. Luck Is No Accident. Atascadero, CA: Impact.

- Mitchell, A. M., Jones, G. B. and Krumboltz, J. D., eds. 1979. Social Learning and Career Decision Making. Cranston, RI: Carroll.

- Mitchell, K. E., Levin, A. S. and Krumboltz, J. D. 1999. “Planned Happenstance: Constructing Unexpected Career Opportunities.” Journal of Counseling & Development 77:115-124.